All Hands, All Lands: Stanislaus National Forest’s Decade-Long Journey To Confront The Wildfire Crisis With Benjamin Cossel

It’s high time we confront the wildfire crisis head-on while looking at forest health from a holistic point of view. In this episode, we talk with Stanislaus National Forest Public Information Officer, Benjamin Cossel, about the MASSIVE undertaking of a historic fuels reduction and prescribed fire project called the "Initial Landscape Investments to Protect Communities and Improve Resilience in America’s Forests." This massive initiative spans a decade, covering millions of acres, and aims to address hazardous vegetation, enhance forest health, and confront the wildfire crisis. Benjamin takes us through how Stanislaus is accomplishing their goals in the forest, sharing innovative strategies to revitalize these landscapes. With insights into the Forest Service's designated landscapes project and the role of Stanislaus, we explore the significance of forest resiliency and reflect on the dire need for holistic forest management. Join today’s conversation and hear the strides we’re making towards creating healthier, more vibrant forests, ultimately contributing to a safer environment for communities and ecosystems alike. This ambitious, 10-year-long, multi-million-acre project is quite impressive - and absolutely needs to be done!

---

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

All Hands, All Lands: Stanislaus National Forest’s Decade-Long Journey To Confront The Wildfire Crisis With Benjamin Cossel

This episode is going to be brought to you by Mystery Ranch, Built For The Mission. If you haven’t been rocking a Mystery Ranch backpack for your fire career, your hunting game, or any of those other load-bearing necessary adventures, you’re doing it wrong. Aside from making arguably the most comfortable, most durable, and most badass Wildland Fire packs in the game, they make a ton of other load-bearing essentials.

Now they also have some new accessories out there. You should swing over there if you’re looking for a new radio holder for your pack because no one likes smacking their elbow or their funny bone on their radio. They made the Talk Box 5000 and it’s a pretty cool little piece of equipment, and it’s affordable. It clips on to wherever you want to put it on your Mystery Ranch fire gear. Go check it out. It’s pretty neat.

While you’re at it, you might as well go check out the Big Ernie Pack as well. I happened to be rocking one of those for my day job with Burn Box and rock that thing while I’m doing prescribed fire. It’s comfortable and it kicks ass. It brings me back to a little bit of helitack days because it is most definitely designed for air operations like helitack, rappelling, or smoke jumping. It’s pretty badass. Go check those out too.

While you’re at it on the website, you might as well go check out the Mystery Ranch Backbone series. The whole Mystery Ranch crew got together. Because they give a shit about the boots on the ground, they decided to make it worthwhile for you to go over there and check out some of their stories. Also, submit your own story for a $1,000 scholarship called the Mystery Ranch Backbone Series Scholarship. If you like what you see and you think you can add to the storytelling game, go over to www.MysteryRanch.com, check out the Backbone Series, and submit your story because there is a $1,000 scholarship up for grabs for your professional development.

The show is also going to be caffeinated by none other than our premier coffee sponsor. That’s going to be Hotshot Brewery. It’s kick-ass coffee for a kick-ass cause. A portion of the proceeds will always go back to the Wildland Firefighter Foundation. If you’re looking for some good coffee or some of the tools of the trade to get your morning started off right or a whole slew of wildland firefighter-themed apparel, look no further than Hotshot Brewing.

You can go over there and check it out and get all your tools of the trade and help support a good cause at the same time. Go over to www.HotshotBrewing.com and check out all of the tools of the trade to get your morning to start off right and all of the apparel and some kick-ass coffee for a kick-ass cause. Go check them out.

Last but not least, the show is not sponsored by and not brought to you by, but it is one of those close relationships I have with Bethany over there at the American Wildfire Experience. I want to show her some love for as long as I possibly can because I believe in her cause and I believe in her mission and she’s got some rad stuff going on. If you don’t know what the American Wildfire Experience is, they house The Smokey Generation. I know for a fact a lot of people out there have seen that rolling around.

It’s pretty freaking awesome. It is a digital storytelling platform telling the story of wildland fire. There have to be over 250 of these stories out there now. It’s preserving the legacy of the folks in the field and the story of wildland fire. Some of these stories even date back to the 1940s. It’s pretty freaking bitching.

If you want a little history lesson or if you want to sign up for The Smokey Generation Grant Program, if you’ve got a compelling story and you’re telling the story of wildland fire through the lens of a video camera or a still camera, through a blog or some animations. There was this one dude out there who made We Move Mountains with spoons and it’s fricking kick ass. They’re a Smokey Generation Grant recipient. The sky’s the limit. Tell the story. It’s fricking awesome. If you want to find out more, go over to www.WildfireExperience.org and you can check it all out. Bethany, you have a kickass organization over there. Keep it up.

---

I hope everybody’s doing well. In this episode, we are going to be talking about pulling our heads collectively out of our rectums, especially when it comes to the whole removing the 100-plus years of hazardous vegetation from the landscape and cleaning up our forests either through mechanical means, hand thinning, prescribed fire, and all that jazz. We’re going to be talking about confronting the wildfire crisis.

I don’t know if anybody’s heard of this. Maybe some of you folks on the Stanislaus have, probably because you’re a big part of it. We’re going to be talking all about the designated landscapes project from the Forest Service. The landscape investments have a ten-year plan to treat upwards of 16 million acres.

It’s a huge project, a huge investment, and a lot of it came from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act. We’re going to be talking with the Forest PIO off Stanislaus. He is going to be telling us all about the program that they have and how Stanislaus is the test pilot for this forest resiliency in these designated landscape projects.

It’s pretty impressive what they’re doing. They’re burning and treating a lot of land. Quite frankly, in my opinion, it’s needed. It’s about time we pulled our heads out of our asses. Without further ado, I would like to introduce my good friend, Ben Cossel. He is the Forest PIO off the Stanislaus National Forest. You all know the drill. Welcome to the show.

---

In this episode, we got some representation from the Stanislaus National Forest. We got a Forest Public Affairs Officer by the name of Ben Cossel. What’s up? How are you doing?

I’m doing great. How are you doing? I’m thrilled to be here.

I’m pumped to have you on the show because a lot of people don’t know and I don’t know why this isn’t getting national attention, but you’re into some pretty hefty RX prescriptions now, and it’s fucking awesome, the scope and scale of it. Why this isn’t national news? I have no idea.

We lost our burn window and so we’re wrapping up at about 4,100 acres burnt. Not only were we able to burn those 4,000 acres, but because of all the resources that we had available to us, we were able to prep an additional 5,000 acres on some of our units up by our Beardsley Lake area so that when fall rolls around, our fall burn windows open up, we are going to be ready to light those up.

Start putting torch to the ground?

Exactly. Work done. Here we go.

That’s the way it needs to be done. I’m a huge proponent of putting more fire on the ground. Fair disclaimer here, this is not going to work everywhere. This is specifically for fire-adapted ecosystems. That’s where it belongs. Let’s get that out of the way. I’m a huge proponent of throwing more fire on the ground, especially when we have 100-plus years of playing God with nature’s garbage disposal ever since the 10:00 AM policy implementation back in 1910. This aggressive strategy has caused a huge accumulation of fuel. What does fire like to burn? Big surprise, it’s fucking fuels.

I’ll take that a step further. On the stand, we refer to it as a fire-dependent ecosystem. It’s not fire-adapted. This area has evolved to be dependent on fire, whether indigenous culture is setting fire to the ground through their cultural practices or the lightning strike fires. On our mid-elevations, we have a fire return interval. I’m getting a bit geeky on you, of about every 5 to 7 years in some of our mid-elevations. You’re probably looking at ten or so years in some of our lower elevations. You have a stand-clearing event every 100 years. This is an ecosystem that is dependent on fire, and we have excluded fire from that ecosystem for far too long.

This is an ecosystem that is dependent on fire and we have excluded fire from that ecosystem for far too long.

You’re not the only ecosystem that it’s been excluded from. These are hundreds of ecosystems across the United States.

You and I were talking about this earlier. The decision to suppress all fires at all times by 10:00 AM was an understandable reaction to what happened in the 1910 fire. You can’t burn 3 million acres in 3 days and not have a knee-jerk reaction to every fire put out immediately. That’s completely understandable. As our science has gotten better at understanding this and as we’re seeing the consequences of some of these devastating fires, people like my supervisor, Jason Kuiken, are saying there’s got to be a different way and we’ve got the science to prove it. A couple of years ago, we started doing all the work on a 55,000-acre project primarily focused along California Highway 108 corridor. For folks who are familiar with the area, that’s like heading up toward Pinecrest Lake from the city of Sonora up to Pinecrest Lake.

You’ve got all these communities built within the wildland-urban interface, and a lot of them are one road in and one road out. You’ve got overgrown forests. Egress and ingress are pretty terrible. You’re looking for a tragedy. You’re waiting for a tragedy to happen. We said we started working on this. We got the NEPA decisions or we did all the NEPA work. We signed our very first decision. We got it signed. The record of the decision was done in March of 2022. We subsequently had two more records of the decision. As we finally got the third record of decision signed and published, the Forest Service came out with the Wildfire Crisis Strategy. That part of that strategy was the identification of what they call ten initial landscapes that have been identified across the Western United States for this additional treatment work.

We went from 55,000 acres to all of a sudden having a footprint of 245,000 acres that are going to be treated. That’s through all of the treatment tools in our toolbox, the hand thinning, the mechanical thinning, and the prescribed wire because ultimately, that’s the goal. The goal is to put fire back on the ground in these ecosystems with the primary purpose of reducing the risk to our communities and protecting that critical infrastructure. Many people don’t realize that 17 miles of wooden ditches and fluence deliver water to all of Alami County and run through the forest. If that critical infrastructure were to go out, we’d be out of water. The utility district I read has something like three days’ worth of emergency supply.

That’s the only rations that they have.

That’s it.

Another thing that people don’t understand about fire, in general, is the long-term consequences. Not a lot of people know that this infrastructure comes from somewhere. When you go to a watershed like the Stanislaus, you’re supplying a lot of water and a lot of other shit to a lot of people. People don’t realize that it’s a long-term fallout. If you have a hyper-destructive, catastrophic wildfire ripped through these areas, you’re cutting off a lot more.

People only think about wildfire suppression costs. They see a price tag attached to that. It’s on the sitrep even. Whoever reports on it like, “This is how much this fire costs,” is that an accurate number? Now we’re talking about infrastructure damage, landslides, and all of the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary effects of these destructive wildfires that we’ve been getting that no one talks about, the true cost.

There are also the intangibles. When we first moved out here, we moved to the community of Mount Ranch. Mountain Ranch was heavily devastated by the Butte Fire. That community has never recovered. The people who came back to their charred homes and landscapes went, “No, I can’t do it. I cannot come back to this.” They walked away. They got their insurance settlements and they walked away, never to live in an area that would be threatened by fire again.

That community, its spirit’s gone. They’re fighting to get it back. That’s one of how many communities across the state of California have had exactly that impact. You have the actual dollar cost, but then you have the cost associated with human lives and communities destroyed by all the things that you can’t put on a spreadsheet that is a huge part of this whole thing we call human existence.

That’s another thing too. Don’t get me wrong, everybody wants their slice of heaven, but you have to live with the reality of you’re not in suburbia, even though fire is affecting suburbia, whether that be directly with the OWI or with smoke impacts from fires. When you get out into the OWI, the hard OWI, I’m talking like your paradises or Greenvilles, just throw a dart at the Western states, any of those small one-way in, one way out slice of heaven places on the map, this is a reality that we have to live with and we have to do something proactive.

It is this regime of over 100 years of progressive fire suppression. Also, on top of that, the lack of fire use, the lack of prescribed fire, the thinning, logging, grazing, and the litany of other shit that goes into this. We’ve caused this problem for ourselves. That’s where you’re on the show here to talk about this project. It’s because we finally pulled our heads out of our asses and we’re trying something.

It was a glorious site when I was riding up the 108, pulling into the fire camp. I’ve got 15 Hotshot buggies and 12 engines. At one point at our height, we had 600 firefighters on the ground at a little place we called Little Sweden up there on the 108 with a full-fledged fire camp. Anybody who’s been on a wildfire would’ve immediately recognized it for what it was, caterers, porta-potties the AT&T emergency cell towers, the whole nine yards.

We are seeing those guys out there participating in the morning brief and doing the information brief. My portion of the brief was I was part of the IMT on that one. The work that all of those guys and gals were able to get out there and do and put fire on the ground, I cannot tell you how overwhelmed I was by the outpouring of support from our community. These people get it. These people understand that there’s no such thing as good smoke. We’re trying to stay away from that messaging, but a little bit of smoke now is way better than a lot of smoke come August and September.

A little bit of smoke now is way better than a lot of smoke come August-September.

They love it. They love what we’ve been doing. My former supervisor and I were talking about this, all told, that we had about 1,000 unique individuals on this prescribed fire. The interesting thing, Brandon, about this prescribed fire is going back to what you were talking about. Pulling our heads out of our asses as part of what we were tasked to do with this on the stand was break the RX system.

Right now, RXs, prescribed fire, is still considered a project. What are all those things that get in the way? What are the policies that get in the way? If we are going to put fire on the ground at the pace and the scale that the Forest Service has said that it’s going to with this wildfire crisis strategy, then we have got to figure out a more effective way to put that fire on the ground.

Part of what we were asked to do was find all those things. Get them up to the Washington office, figure out what they are, and let’s figure out how to get around them and, more broadly, how to change them so that when they go do this, those roadblocks aren’t in the way. They can put the amount of fire on the ground that they need to have that impact that we’re looking for to try and start mitigating some of the worst impacts of these catastrophic fires that we’ve been seeing.

That’s another thing too. This is paving the way for not just exclusively putting fire on the ground. You’re trying to find a way to streamline all these processes to put fire on the ground and reintroduce nature’s garbage disposal to Mother Nature here, but it’s more complicated than that. An effect of that would probably be streamlining the process for people is to get in the forest to do mastication work, fuel reduction, lop and scatter, and all the other shit that needs to go into this.

It’s not like, “Throw fire on the ground. Congratulations. Good day.” There’s a lot of shit that people don’t realize. Especially the fire operators that are reading this are going to have a lot more knowledge of it than Joe Blow public who’s reading into this. What about that effect? Is that going to be streamlining it for them as well?

One hundred percent. For the non-fire operators out there, by the time you get to a point where you’re tipping torches and putting fire on the ground, that’s your fifth or sixth entry into a unit. Going back to exactly what you said, there’s so much prep work that goes into getting a burn unit ready to tip torches. It is that mastication, it is that hand thing. It is putting in those handlines. It is making the containment lines. It’s all those things.

It is the communication saying, “We’re going to do this.”

There’s an entire overhead apparatus that comes into effect and becomes part of the equation when you’re doing this. To get at your point, that is exactly what the Stanislaus Landscape Project is about too. It’s figuring out those processes and what are those tools that we already have so that we can not only put good fire on the ground or tip torches and put fire on the ground, but how do we find those contractors who have the heavy masticators to go out there and do that mechanical thinning that we need to be done?

Where are those crews that are out there that can go out there and do that hand thinning when all of our Hotshots are on a fire up on the Klamath not available to us? How do we get those crews out there to be able to do some of that hand-thinning work? What we’ve come to and what we’re leveraging is partnerships. It’s working with organizations.

There’s an organization called Yosemite Stanislaus Solution. They came out of the 2013 Rim Fire. That’s environmentalists. You have the Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center working alongside SPI, Southern Pacific Industries, which for those who don’t know, is one of the largest logging industries here in the Sierras.

These people definitely don’t see it quite eye to eye, but they realize the value.

They’re on the same page. They came together after the rim fire and said, “If we don’t figure out a way to put our differences aside, there’s not going to be a force to argue over.” They started focusing on what were their commonalities. Out of that, they now have 36 different organizations that are a combination of environmental groups and industry professionals working together.

One of those within that is the county of Tuolumne. With that, we were able to utilize a partnership tool called a Master Stewardship Agreement, whereby there’s a $1 per $1 match. The Forest Service in Tuolumne County goes into this Master Stewardship Agreement, and let’s say we give them $5 million for a project. Tuolumne County then has to come back and either dollar-for-dollar or in-kind returns match those funds that we were given.

It’s not an exact thing. There are all sorts of lefts and rights. I’m oversimplifying it for the point of this conversation, but hopefully, folks get the point. Tuolumne County has as much skin in this game as the Forest does when we’re doing this work. Because they manage that Master Stewardship Agreement, they’re responsible for awarding the contracts. It’s not rocket science for anybody to understand that it’s easier for a county to execute a contract than it is for a federal agency.

A lot less red tape. This goes with any big bloated bureaucracy. The Forest Service is huge. That’s a lot of people. That’s a lot of moving things. It’s not a very easy ship to pivot. The Bureau of Land Management is much smaller, but you can’t pivot that thing as fast. When you get into these counties and municipalities, if you are using them as a contracting vehicle to get your stuff done and it’s mutually beneficial, then why the hell aren’t we doing that?

For a lot of the counties, and this is a thing that we’re working on as well, it might be that they don’t have the financial resources. There are a lot of other partnership tools that we have. There’s a good neighbor partnership agreement. I know a little bit about partnerships. It’s not my bread and butter, but we have these different tools.

The biggest reason I’ve heard some counties say that they can’t go to some of these larger ones is exactly that. They don’t have the financial resources. They don’t have a tax base. Whatever the issue is, they don’t have it. One of the interesting outcomes of this Master Stewardship Agreement with Tuolumne County is that they’ve been able to leverage that. It’s been a major check for them.

When they go out and apply for community wildfire defense grants or all of the different grants available either through Cal Fire or the state, the fact they have the backing of the United States Forest Service and the Stanislaus National Forest with them, grants are awarded based on points. A reviewing agency takes a look at it and says, “Your application scores, you’re up,” and so on and so forth.

That’s a huge boost to their points when folks are looking at awarding those grants. They’re able to qualify. I tend to think of it as that they are punching way above their weight. God bless them. They have received so many millions of dollars in this program to supplement and work with the work that we’re doing. The amount of money that they’ve been able to secure has been amazing.

It’s compounded by more money out there with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. You’ve got local grants, state grants, and all these avenues for getting this done. I was reading through the Wildfire Crisis Landscape Investments, the Controlling Wildfire Crisis doc, because this is an amazing document, by the way. It’s not just you. I’m looking at all of these landscapes, and there are 21. The ones that are listed on this initial page, the acreage on here is astounding. You guys have 300,000 acres that you need to treat over the next ten years. The total acreage on here is a lot.

We’re in the millions.

There are multiple tens of millions almost. We’re over 10 million acres easily.

Back to your point too, the initial funding seeds for this are from the Bipartisan Infrastructural Law and then there was an additional wave of funding in the Inflation Reduction Act, IRA. That’s where a lot of the funding for these projects is coming from. As we see it, the message is clear. Not only has our chief but Congress has said, “We are giving you money to treat lands and to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires to these communities. Go do it and succeed.” Those are our marching orders, and we are doing everything in our power to execute on. Thus far, I’d say we are doing a pretty darn good job on it.

That’s the thing too. This is such an ambitious field treatment plan. It’s mind-boggling. The best way I think I could put it is I was talking to JK Boots. I was on one of their podcasts. I was saying like, “There are 640 million acres of federal lands managed by the federal government out there between the Forest Service and the Department of Interior.” All of those pretty much have some wildfire risk in it. Some are going to be greater, and some are going to be less than others.

If you were to set up on top of whatever mountain you want to pick and put that mountain right in the center of that 640 million acres and look in a 360-degree view around you, you would never see the end of that amount of land. That is a lot. It’s no surprise. That’s the thing that I’m getting at. We need all the help we can get. With a plan that’s already penciled in, it’s already there. The funding for these landscapes is already there. You’d have to be naive to say that this is a problem we can hire our way out of.

However, like you said, there, we’re taking all of our collaborators, we’re taking all our boots on the ground, and we’re taking everybody that it can possibly take to treat these lands. That said something because I realized that it’s going to take all hands on deck to treat the amount of land that we need to treat.

There is no way. I keep going back to the words of my forest supervisor. His whole point has been on this one too. He is like, “Even if we could do this work by ourselves, which there is no way in hell we could, we all get that, but why would we even want to? We need to engage our stakeholders. We need to engage our collaborators. We need to bring those people on board because this is their land too.” The Forest Service had a little bit of a history back then of being like, “We’re the federal government. We can do this, deuces.” They would go off and do their work.

At least on the Stanislaus, I’m fairly certain that this is across the agency, have said like, “That’s not the way to work anymore. If we’re going to get this work done, we cannot do this alone. We do not have the resources, we do not have the dollars, we don’t have everything. We need everybody.” Thinking about it, one of our major partner groups, and as part of YSS, Yosemite Stanislaus Solutions, is an organization called Tuolumne River Trust.

We work with them to put in some of the pre-hand lines, the containment lines. They have crews from, whether it’s the AmeriCorps or Job Corps, those young kids coming out in the summer, they put those crews to work, putting in those hand lines prior to us going in that coming fall or whatever to do to put that fire on the ground.

It’s increasing our capacity. Turn on the news and you’ll hear a story about how understaffed the Forest Service is. We have to increase our capacity and we have to operate. We have to treat these lands at the pace and scale that the wildfires that are consuming the Western United States are burning. You’ve got Dixie at almost 1 million acres. Can you even begin to think for a minute of a force being able to treat a million acres? No, we can’t. We’re not there. If we’re going to do 300 some odd thousand acres over the 10 years, if I’m doing some quick math, we probably need to be doing 30,000 acres a year. That’s a lot of treatment.

Anything to prep a unit, anything to stack sticks, burn piles, put fire on the ground as far as like a broadcast burn, mastication, all that stuff. That’s still treatment.

All of it is getting it to the point where we can burn. We were talking earlier about the fact that like, I’ve had 1,000 unique firefighters and overhead people out here on this fire. If we’d been doing this right for 100 years, it shouldn’t need those numbers. Low-intensity fire on a unit, that’s something a crew and an engine could probably handle if we are doing it correctly. If we’d been doing it the way we were supposed to, if we didn’t have all that forest stuff and forest floor buildup, if we didn’t have all the snags out there, all the hazard all the stuff that we talked about that goes into prepping a unit.

If that stuff had been taken care of correctly over the course of Forest Service history, this would be a problem that we wouldn’t need as many people at. We’re not there. We need the people. A good friend of mine tends to refer to it as like all hands, all lands. Not only is this about us as collaborators as the Forest Service, working with our partners, all this stuff to get this work done, all these homes that are built into the OWI and everything, they got to do their part too.

There’s a definite personal accountability thing, especially for the folks living in the OWI, that slice of heaven. You got to take care of it.

We’ve got to work with our state and private lands people. We need to work with our state agencies to get to those private landowners and help them with creating their defensible space. It’s all well and good. If I’m going through and I’m treating all these acres and I’m making a fire break around the community of Cedar Ridge, if it punches through a private lands hole, that community’s still in trouble.

We all have to work together to address this problem. I’m making the point. I’m screaming from the mountaintops that the Stanislaus is well underway in starting this process, in getting this work done. We’re not alone. There are 21 landscapes in the Western United States that are doing this work all in varying degrees of where they are and as far as we know how far underway they are. We’ve been at work now. We’ve been doing this since we got our record of decisions signed. We started year two of our ten-year commitment.

You guys are doing a hell of a job. That’s another thing too. I want to point out the severity of the fuel buildup and also the scope of work. You guys are managing 300,000 acres. It’s going to say differently, but you’ve already treated some, so we’ll call it a little bit less than the 300,000 acres that you guys need to treat. You guys are already breaking the system and trying to figure out where it’s weak. That’s based on 300,000 acres. If you look at the front range of Colorado, they’ve got 3.5 million acres of designated lands to be treated. That gives you an idea of how complicated this shit is and how long it’s going to take.

At least when we’re thinking about it, at least when we’re talking about it, ten years, that’s the initial investment. That’s the drop in the bucket to start this process. We have 100 years to undo and we’re not going to undo that in 10 years. Will we be on a good road at the end of 10 years? Yes, we will be. No one believes that we can do this work for ten years, call it a day, and go home. We don’t ever have to worry about wildfires ever again. We’re done. We solve the wildfire crisis. No. No one believes that. Going back to that fire return interval. We burnt around the town of Strawberry and we burnt in Dry Meadow.

We all know we’re going to have to go back in there in 5 to 7 years and burn it again. Now we’ve treated it, now we’ve done the work so that we can go back in there and do that low-intensity broadcast burn with far fewer resources and handle it at an affordable rate that makes sense to the American taxpayer. We’re all using taxpayer dollars or using taxpayer funds to get this work done. I’ll tell you, I’d much rather see it being used in a proactive fashion than the millions that we spend on suppression efforts and throw everything we’ve got at suppression when we’re at that point. If we could throw a couple of million at preventative work, that would make my heart happy.

It’s a hard sell, though. This is the conversation that always comes up when I’m trying to explain how much it’s going to cost, suppression versus prevention. An ounce of prevention is worth its weight in gold. I’m stuck on that. Is it expensive? You’re in the business of selling what-ifs because typically, your voting demographic doesn’t give a shit about wildfire and it sucks. They don’t give a shit about it until it’s impacting them with smoke or their favorite national forest is burning to a crisp.

That’s when they care. For the most part, it’s a faraway problem and it’s not their direct problem. How do we wrap the messaging around this whole package saying, “Good fire is good.” Why would you want to have a Caldor or a Dixie or an August complex or a hog fire? This is generational damage because the fuel loading is so extreme on some of these landscapes that it burns so hot that it burns the microbiome in the soil. It sterilizes the landscape down to the mycelium, past the mycelium layer and nothing will grow back. It’s generational damage.

Not only is it generational damage, but thinking about my forest. You have Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. That Hetchy Reservoir flows down through the Tuolumne River. The Tuolumne River is in my forest. Hetch Hetchy is the primary water source for the City of San Francisco. If the Tuolumne River is all of a sudden degraded because of a wildfire, all of the different things that can happen to a watershed because of a wildfire, all of a sudden Hetch Hetchy is non-operational or has to spend extra time purifying. Whatever the consequence is, dear San Francisco, you’re having an impacted water system all of a sudden.

Those are those secondary or third-effect fallout damages that no one ever thinks about.

You don’t see it. Everybody sees the fire. We see the heavy timber burning in the night sky. That is what we all think about. That’s why it’s called an ecosystem. There are so many other components to a forested ecosystem to a desert ecosystem than what you can immediately see. There are three major water sources that run through the Stanislaus. You have the Mokelumne, Stanislaus and Tuolumne. That’s also how we’re divided in our Ranger districts. You also have the major California highways of Highway 4, 108, and 120. The romantic in me likes to think we’re divided by the rivers. I don’t like to think of the fact that we’re divided by roads.

I tend to think of us in rivers. Any one of those water sources, those watersheds are impacted by fire, that’s going to have literally downstream consequences to communities across the State of California. We have electrical systems right. That Hetch Hetchy is also a power producer. The power that goes to San Francisco. If we have transmission line issues in the forest, transmission lines get destroyed or something like that, all of a sudden, San Francisco’s out of power. There are all of these impacts.

You can’t come up now for Memorial Day, spend your weekend out on Pinecrest Lake because Pinecrest Lake doesn’t exist anymore because a fire tore through it and it’s not there. We have all of these individuals that live in an urban interface and they rely on the fact that a wild interface is in their backyard. Two hours up the highway and they’re in a wild place. Not if it burns. Not if we don’t have it anymore. It becomes incumbent upon all of us. If you love public lands, you need to care about this. This is going to have an impact on all of us.

That’s another thing too. People don’t realize that a lot of these communities are heavily dependent on tourism as well. This is how people make their money. That’s how they pay their mortgages. That’s how they pay their fucking taxes. These tax dollars go back into the land con conservation. Being good stewards. You’re trying to implement these plans to be good stewards. People don’t understand this. It blows my mind, seriously.

We had a pretty heavy snow and rain season up here in the Sierras and proportions of Highway 120, specifically the portions leading into the northern entrance of Yosemite National Park, the roadway fell away. They had to keep that entrance to the park closed for about six weeks longer than normal. All of those communities up the 120, Groveland, all those places. Even the city of Sonora that is used to that traffic coming through on their way up to Yosemite, the hotel taxes, the people spending money at the bars, at the restaurants, all of that is gone. That’s on top of the already degraded tax base that we had because we got out of two years of COVID restrictions. Talk about a one-two punch to a small community losing that tax base.

It’s back open. Traffic’s flowing again. Everybody’s happy and we’re good but that’s exactly it. Those are the sorts of impacts. A six-week impact might not sound like so much, but it’s huge to a town like Sonora or a county like Tuolumne. You take the Iron Horse out there in Groveland, they’re struggling. They’re going to make it. They’re going to pull through, but there was a moment there where they didn’t think so.

This narrative is replicated across every small destination and mountain town across the United States, anything that’s been impacted by fire. Look at Frenchman Reservoir. I forget what fire was, whatever fire that was, it burned completely around Frenchman Lake. That super sucks. Now it’s devastating the communities. I can’t even imagine what it would look like for uninsurability. Look at the State Farm thing. State Farm pulled out of the State of California. They will not insure.

Most of us in this area are probably left with the FAIR Plan now. That’s what we’re getting to. That’s our only option. I live in Sonora. I live in this community. I love this environment. It’s getting harder and harder every year to live here. You and I were talking about the fact that the Sierra Nevada is a fire-dependent ecosystem. Anybody that lives in this environment and who’s been here for more than a year understands that. They know that. They know that there’s a certain amount of risk that comes with it.

A whole bunch of those of us who live in California live with some level of risk all the time, whether it’s an earthquake in the Bay Area or a wildfire out here. Whatever the issue is, all of us who live in California live with some level of risk. That’s not what’s making so many people leave these small towns. It’s exactly what you said. They can’t get insurance or their insurance is so astronomical, there’s no way in hell they can afford it. People paying $6,000, $7,000, or $8,000 a year for homeowners insurance is ridiculous. That is untenable.

That’s the thing, though. We put ourselves in this situation but gaining widespread adoption to fix these fuckups that we’ve made for the past 100-something years, I think it’s finally starting to take hold and this project, this 300,000 acres of putting good fire back into the landscape, that’s proof. You wouldn’t have been able to do it unless you had some public support.

If there’s a silver lining that came out of the Dixie fire, and this is my opinion, it is the fact that that smoke made it to DC. It made it to New York City. People back East finally went, “This might be a problem that we all have to take a look at.” We started seeing some action. We started seeing some movement. While we have all the funding for this work in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and while we have some of the additional funding in the Inflation Reduction Act, people back East finally started realizing that this is a bigger problem than just a Western problem. We’ve started working on it.

We’re starting to do that work. In region five in California, of the 18 forests we have out here, something like 10 of them are in landscape with a project going on. Don’t quote me on those numbers. Somebody in the comments will correct me on that exact number or whatever it is. We have a significant amount of forests in Region Five that are now a landscape project showing that commitment to this work from the forest service from Congress that this work needs to be done. That work stretches all the way down from Cleveland and the South to the six rivers and the Klamath and the Shasta Trinity in the North. Just about every forest in between has got some impact.

We’re doing this work and we are figuring it out. We are figuring out how to make this system work in such a way that we can get our force back to a system. The buzzword’s resiliency. I realize that that’s like becoming a sustainability bingo word. The truth of the matter is that’s exactly what it is. It’s building resilience systems. It’s building a resilient force. We get five years down the road on our highway one-way corridor and God forbid we got a lightning strike on one of our treated areas. Low-intensity fire. That’s exactly what we need. That’s what we want.

I have thin forests so that my mixed conifer forest isn’t fighting for the resources we’re losing because of climate change, the drought conditions that we continue to see, and the bark beetle killing off all of these things that are impacting our trees out there. By building these systems to be resilient, they can knock on wood, and weather through some of the worst conditions or the worst that Mother Nature has to throw at them in climate change. If you’re not fighting for resources, you have a much better chance of survival. That’s basic math.

Stanislaus National Forest: By building these systems to be resilient, they can weather through some of the worst conditions or the worst that mother nature has to throw at them in climate change.

That term climate change is so damn polarizing. That’s the thing that I don’t get. Am I a climate change denier? No. Am I a climate change believer? To some degree, I’ve seen some pretty gnarly shit on the ground. Do I think that humanity has the capability to change the climate to some degree? Absolutely. You’ve seen it.

What I like to do when I’m trying to hammer down on this argument of like our forests, our resiliency built into our national forest or our landscapes or whatever, I try and remove the climate change term from that argument. Now everybody can have a conversation about something that’s not polarizing, like real shit that’s in front of them.

What if we were to replace that messaging? Instead of climate change, which is a factor, but it’s one of many factors, what if we harbor down on the environmental change? Humanity has a direct impact on its environment and everything around us. There’s no question about that. If you pollute a fucking river, you’re going to have dead fish. Cool. That’s environmental change. When we have these 100-something years of environmental change that we had a direct hand in, we can explain our fight a little bit better without the politics. That’s my opinion. I think you guys are changing the environment right now by putting fire on the ground.

Also, thinning and thinning the forest to a healthy density that our scientists have said is more appropriate, that looks more like what that forest looked like 100, 200, 300 years ago by the best available science. You’re right. I feel ultimately, for me, arose by any other name would smell just as sweet. Things are happening in the landscape. Call it whatever we want to call it.

The truth of the matter is if we don’t react and if we don’t do some active management and try to bring these systems back into some form of balance, we’re going to have catastrophic results. Whether that’s in large stand die off due to bark beetle or if that’s a catastrophic wildfire or if that’s trees that die because of drought stress, that’s all happening, so we have to do something.

That’s the thing. It’s no surprise that back in predating written history, essentially until the colonizing of America or any other indigenous culture, it fucking sucks. If you look at every indigenous culture across the entire globe and where they reside, they have all used fire for ecological benefit. That’s the reason why we have trees in your neck of the woods and a little bit South of you in the Yosemite area that are predating written history. It’s because they’ve been managed.

We excluded that knowledge. We remove that knowledge from the landscape to our own detriment. That’s another one of these things that are baked into this whole landscape project that we’re talking about. It’s that acknowledgment that that exclusion wasn’t the best idea. We are working where we can and not everywhere has the opportunity for various reasons, but where we can, we’re working so closely with our tribes to try and start reintroducing cultural fire alongside prescribed fire in those environments.

I know there’s a lot of work being done up on the Six Rivers with the tribes up there. Wherever people are able to, wherever possible, work with our tribes to start bringing that historical knowledge back to the landscape, back to the land that they managed for generations. We took it away. We took it out to our own detriment. I am glad to see that we have pivoted on that and that we are going in the direction back to the reintroduction of cultural fire.

It needs to happen and it needs to happen at scale. I think that’s a good thing about the project that you have going down there. This is a very ambitious goal. I think the biggest prescribed fire that I’ve ever been on was maybe 5,000 acres and that was multiple units. Now we’re going to 30 a year, 10% of your total goal a year. Thirty thousand acres a year of treatment.

That’s the bottom line. That’s basic math. I don’t want my poor resource manager staff officer to hear this and have a heart attack. I love you, Michael. Don’t worry. I’m not making any commitments for you or anything of that nature. Basic math tells us that if we’re going to treat 305 acres or whatever the number is over ten years, if we’re hitting our numbers, we should be looking at an average of about 30,000 acres treated a year through all the different methodologies that we have at our disposal.

Let’s get clear about that too. There’s no one silver bullet. Indigenous burning, cultural burning, RX fire, all that stuff, that’s great. It’s a safe way to scale treatment safely using fire. I get that but it’s not appropriate in all situations. You’re not going to be doing this shit in the middle of August.

That’s exactly it. We have all of these tools in our toolbox that we’re utilizing. That’s like we were talking about, whether it’s mechanical thinning through masticators and stacking piles and all of that or hand thinning, all the different tools that we have at our disposal. An interesting thing, too, that popped into my head as we’re sitting here thinking about this. Anybody who’s ever worked in fire is familiar with piles. We all know, we’ve all seen piles. One of the things that we’re also doing with this project is that the forest has written letters in support of those biomass companies who use that tertiary non-prime lumber for additional wood products.

Gasification for people’s pellet stoves. Removing that biomass from the forest without us having to burn it. Building another industry, giving people jobs putting people to work in these rural communities without having to burn all those piles of logs because now we have an industry that can support that biomass removal. That’s another component of all this. Was it the ‘60s or the ‘70s when in a lot of these mountain towns, the sawmills started closing down because we changed how we were approaching timber?

We are looking at increasing that production here in Tuolumne County and here on the Stanislaus because of the work that we’re doing with thinning, with taking down those trees and getting them back to a stand density that our scientists have told us is appropriate. That’s creating a product for those markets, whether it’s the SPIs of the world or it’s some of these other still nascent companies that are building those secondary tertiary products off of that biomass.

There’s a lot going on here. I was telling you at the beginning, we called it social and ecological resilience across the landscape. That takes a look at the totality of the community. It’s not just the forest. It’s not just building a resilient forest. It’s building an entirely resilient ecosystem. That means the communities that live with us.

It's not just building a resilient forest. It's building an entirely resilient ecosystem. That means the communities that live with us.

That means working with our community colleges to help them develop the programs, providing like those, that exact wording and guidance so that when a student goes to their program, they have all the words in there that OPM is looking for when they go into USA jobs to apply but building up that capacity for the masticator owner or the heavy equipment operator, getting those workforces. We are giving kids in Sonora, Long Barn, and Twain Harte a reason to stay in these rural communities. We’re working with the local community colleges to build those programs for them so they can get done. I don’t know if somebody who runs a masticator makes it, but I promise you it is not minimum wage.

Especially once you get up to having a little bit of experience under your belt and you can run that masticator and effectively, you’re doing pretty okay for yourself. That’s, that’s me being a little glib and understating. Those operators are making damn good salaries and they now have a reason to stay in these rural communities. Social scientists have been talking about this forever, the brain drain from rural communities to urban communities.

I love urban communities. I lived in San Diego. I lived in San Francisco. I’ve lived in cities in the East, but there is nothing like my rural community of Sonora. I’m looking out my back door right now out onto the 4 acres of property that I have in the orchards that we’re putting in. I can’t think of anywhere else I want to be. More than that, I have twin boys. I want them to have somewhere to go to, a reason to stay here. It’s their choice, but I want them to have the ability, if they want to stay right here in Sonora, raise their families, and have a viable path to becoming an adult and starting a family.

That’s one of the biggest lies that we’ve ever been told, especially my generation. I want to say it hammered down on the millennial generation. You have to go to college and get a degree, a Master’s degree at a minimum to be successful in life. That’s bullshit. You can run masticators. I know what masticator operators make. They make anywhere from $25 to $30-something an hour.

That’s entry-level. Some of them have benefits. That’s a good living. It excels you in other areas that you can go into. You can start your own business. You can do this, that, and the other. You can learn how to wrench on the damn things and fix them. It’s like the old adage. Why sell guns when you can sell bullets?

That’s the thing, though. It’s taking a holistic approach to land management and then implementing it into this forced resiliency plan that you’re working on. You’re an active participant. The good thing about that is it expands the communities, gets people hired, and gets jobs back into these rural communities. It spreads out because you don’t have enough people in that rural community to sustain the amount of 300,000 acres of whatever treatment you apply to the land. It’s a good practice to have an all-hands, all-lands approach. It’s a holistic top-down thing. How do you scale that, though? That’s a crazy thing. We have all these 21 landscapes that are target identifications for these fuel projects, but this needs to be replicated everywhere.

In my heart of hearts, I completely agree with you. We’re doing that exact work on the Stanislaus as well. The Stan is 895,000 or 910,000, depending upon what allotment of wilderness we’ve got this particular year. You’re still only looking at about 25% of the forest that we’re talking about as being able to treat. I’ve got interdisciplinary teams right now on the forest working on expanding that to the North and to the South of that existing landscape footprint. This has to be done on the entire forest. It can’t be on the Highway 108 corridor. If we’re going to do this correctly, if we’re going to walk our talk, we have to do this across the entire landscape.

I’m with you. I want to see this done across all forests in the United States, but what I have even a modicum of input in is what’s going on in my little slice of heaven in the Sierra Nevadas. That’s what I’m doing. With everything that I have with my whole heart, I am invested in this. I am fighting the good fight to support my folks on the ground.

Not only my firefighters but my botanists, animal biologists, hydrologists, and all the people that make up this team that do this work. You can get to a point where you have a NEPA decision done so our firefighters can get to work doing that thinning work and treatment work. It is all hands. Everybody in the forest service and our communities has a role to play in this. Come talk to us. We will figure out a way to put you to work.

Evangelize a bunch of people to put fire good land practice and good stewardship to the landscape.

That’s what we’re going for. You walk around morning brief out there at the fire camp. You start talking to some of these 22 to 25-year-old kids, this might be their first assignment, their first year on an engine. You start hearing words like historical, part of history, radical change, the forest service is done a 180, all these words that these kids are banding about. That look in their eye when they realize that the work that they’re doing as part of this landscape project is going to be written in the history books. You can see the going in their eye and they light up and there’s extra purpose in what they’re doing.

It’s amazing to see, as the information officer, both for the INT and for the forest broadly, to see people doing this work and seeing it resonate with them. We started this May 25th and so not a whole lot has been going on across the Western United States. For a lot of folks, they pulled up in here and they’re like, “What the hell is this? I’m on an RX fire in on the Stanislaus in May.”

Probably pissed off about not getting paid.

I cannot go down that road.

All the fire operators reading this know what we mean.

They get there and do that very first-morning brief and see how close we are to the community of Strawberry or how close we are to these 645 special-use cabins that we have out there in Pinecrest. As the guys are tipping torches, the family is sitting out on their back porch taking pictures of them doing this work, it’s amazing.

I keep telling everybody, “I know I sound like I’m spewing hyperbole, but we are rewriting for service history with this work that 50 years from now, there will be books written about how 2022 or 2023, whatever number of historians end up settling upon was an inflection point for the Forest Service, they win a different direction.”

Think about this too. This is very much a pilot program, in my opinion. This is a test. This is a big ambitious test across multiple forests across the 21 landscapes and varying degrees of acreage targets. The cool thing is that say, in five years, we figure out a recipe. We figured out a system to get all this stuff down. We figure out how to cross our red tape boundaries. We figure out our efficiencies. We figure out how to make all this stuff happen. Now you have a plan and a vehicle to do it and that could be replicated by whoever picks it up. It’s going to be more complicated than that. I’m taking this reductionist view towards this whole thing.

Once you have that plan and what works and what doesn’t, you can formulate a plan and replicate it across any forest. That has global effects. That’s the big thing that I see about this, is that if we figure out this recipe for success in treating landscapes at scale, we wouldn’t have the situation that we would have in Canada. We wouldn’t have a situation like black summer in Australia. We wouldn’t have this, that, and the other. We can get ahead of the curve.

Can we prevent all of it? Fuck, no. That’s dumb to say that. It’s naive to say that we have to have fire. We have to have a fire on the landscape, but we realize we need to realize that we can have our say in when it happens or where it happens. The infrastructure is at risk. Why aren’t we doing this? This has big implications.

Feeding off of what you were talking about, one of the things that the team that came up with the initial project and then the landscape project we’re proud of and spent a significant amount of time figuring out was how to make what we were doing modular so that any forest system or any forest could pick this up. You don’t have to do it exactly the way we did it, but here’s your framework.

Here’s what a framework looks like between the partner activation, the partnership tools we have for the finances, and all those we’ve discussed. It is a modular system so that any forest could pick this up, implement it, and start work. There’s the deeper process and all the details. The devil’s in the details but get to work. Get to work on doing this work because the framework’s been done for you.

That’s another thing too. If we are so hell-bent as an agency that the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management or I’m going to say the Department of Interior in general, we’re so hell-bent on providing a workforce that is going to be year-round, here you go. This is one of those plans. I’m not one of those people that wants to be in a year-round workforce fighting fire, because I’ll be burnt out. Come that 26, don’t get me wrong, for the people capable and willing to do that, now we’ll have fire resources, less fire severity, less intensity. The fires that we do identify as a management strategy, we can apply a management strategy to. We can identify those more easily. It’s huge.

The important thing to remember is that it’s 100 years of getting ourselves into this mess. It’s not going to be fixed tomorrow. I’m with you. Everything you said, that’s the goal. That’s where we’re trying to get to. That organization that is effective has all of those different components so that we are managing these landscapes, all of them, all the public lands, in such a way that we’re not burning anybody out.

The important thing to remember is that it's 100 years of getting ourselves into this mess. It’s not going to be fixed tomorrow.

We’re not constantly running from one catastrophe to the next. We’re working at the pace and scale that people can have lives, that people can go home. They can do an RX burn started at 7:00 or wherever the test fires go and be home for dinner. We’ve done it in such a way that they’re able to. We’ve gotten the landscape back to a healthy point where they can,

Think about it, even if with actual wildfire starts, whether that be roadside or human-caused or lightning-caused or whatever, imagine if you have this system of employees of people, contractors, stewards, forest service employees, DOI employees all throughout the land doing all of this work throughout the winter. Now you have systems of checks. If a wildfire does start, it might run into another prescribed burn. It might run into an already established unit with the line around it. The lights are on. This makes a lot of sense.

This is what we need to be doing. It’s like you said how the entire United States isn’t aware of this work being done beyond me. That’s part of why you and I are having a conversation right now. This needs to be everywhere. This needs to be the future of how we are managing our forests so that all of us can continue to enjoy our public lands and we’ll not have to worry. Wouldn’t it be awesome if State Farms said, “You all did a lot of work. We’re coming back. You have reduced the risk enough that we feel like we can come back into your state and insure you again.”

Back to the insurance thing, too, if they pulled out of California. What’s stopping them from pulling out of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and even Nevada?

I’m terrified to think it’s a matter of time. Pulling out of California was the first big shock to the system. I’m afraid it’s a matter of time.

It’s only a matter of time. If we do the work and pay and front load the costs of that, we might have a more sustainable future with insurance and all these other complications, these long-term scaled effects of wildfire. It’s not just suppression costs. It’s not the amount of aviation resources you throw at a fire. We’re getting to a point where we’re so overstocked and forests or we have so much dent down or beetle kill or whatever that you can throw all the resources in the world at it and it isn’t going to stop. Look what happened to Greenville. That’s what we need to prevent. This is the solution. Scaling treatment way up.

It’s a hard thing. It’s like the messaging because a lot of people, the general public, pick up on this episode and are reading this in LA or San Benito or wherever that’s not fire-impacted. They see the smoke and stuff. How do we start getting to preach a good word about effective stewardship and the importance of fire on the landscape? Even like fire for resource benefit. Using wildfires that are doing their thing naturally and it’s not destructive. How do we hammer down on the importance of this so we don’t have that generational damage and all this other stuff, these all the way down the line catastrophes from wildfire?

That is the challenge that all of us are facing. The only thing I can think of to do is, like we were talking about earlier, I plan on dying here. I have a plot picked out on my back 40. My wife’s got a plot next to me. This is where I call home. I want my twin boys to be able to grow up and live here and enjoy this place. I’m going to do everything in my power to protect this. My friends don’t have a lot of experience with the wildland interface, with dispersed camping, and hanging out at Pinecrest. My friends are from San Francisco or the Oakland area.

I’m thinking of a particular friend at the moment. I want them to understand that there is a significant amount of work being done to fucking save this place. One of the reasons that this landscape got picked is because we’re one of the last areas of Sierra Nevada to not have seen a significant wildfire in the last 100 years.

You do not understand what you’re looking at. You are looking at that natural beauty that hasn’t been impacted yet. We want to keep it that way. We want it to stay that way. We want to be here. They have this whole idea of doing it for the benefit of seven generations. I want to take this out for 100 generations. I want this landscape to be here today, tomorrow, for as long as the Earth will continue spinning around the sun. I would besiege all those folks who don’t live in this interface, who come up here on Memorial Day weekend or whatever. Whenever you come up here to recreate in the forest, understand we’ve got a lot of work to do. We’ve got a lot of catching up to do.

It’s not going to be brilliant. You’re going to have some smoke on your holiday weekend. You’re going to see the engines and all the different apparatus on the already crowded roadway. It took us 100 years to get here. It’s going to take us some time and a lot of work to get it back to a state where we need it to be.

It took us 100 years to get here. It's going to take us some time and a lot of work to get it back to a state where we need it to be.

Bear with us. Have a little bit of understanding and take the time to learn about fire ecology, fire-dependent ecosystems, and the history of the Sierra Nevada. Whichever landscape you happen to call home or recreate, take the time to learn a little bit about the ecological history of that place you go to, especially if you live in the Western United States. Fire is inextricably linked to those landscapes. I would say it further that we got a lot of work than for you to get it back.

I would even go further to say that if fire is inexorably connected to humans, we would not have evolved as the species that we are now without fire and learning how to harness it.

It’s as elemental as water. It’s as elemental as wind. It is a part of this. That’s it. We have all got to learn how to thrive with fire. Not just live, not just walk, but thrive. This is part of our ecosystem. This is part of our landscape. We’ve got to get it back to a place where the land can take it the way it used to take it in that healthy, low-intensity open-up the giant sequoia cones way that it used to. If we’re not, we’re going to see the giant sequoias go away because there’s nothing to replace them. We’re going to see all of our incense cedars, our redwoods, and all those trees that depend on fire in some way, shape, or form.

For soil health, the carbon that’s added back into the soil from fire in the form of biochar. I would ask people that this messaging isn’t perfect. I have to keep reminding myself that that fire is a blunt tool. As such, it’s not an easy message. Take that time, I would say to folks, and learn about your ecosystems. Go talk to anybody, any forest working on one of these landscapes and I promise they will talk your ear off about this work. Let us get some work and we’re doing our best to make sure that California and all of our public lands remain the treasure that they are

One thing I do want to ask you, too, is how we get people over the fear factor of fire. Look at the knee-jerk reactions. Look at Hermits Peak, the stuff that happened in the desert Southwest Region. Some of them escaped wild or escaped prescribed fires, but that’s the thing. It was going to either happen by a lightning strike or it was going to happen by an abandoned campfire.

That’s the thing I think that people don’t realize and they’re scared shitless about this catastrophic effect that these wildfires do have. The risk element’s going to be there, but it’s going to be no different than driving your car. You can get in a car accident and can equally step off the curb and get plowed by a bus. Sometimes shit happens. How do we get people over the fear factor of wildfire or planned fire in cultural fire, whatever?

Whatever the descriptor is that we’re using, I think the truth of the matter is you are never going to be able to completely remove risk from the equation. That’s not possible. I don’t think people realize the level of expertise that one has to have to be a burn boss type one. It’s not right. Even a burn boss type two, the amount of qualifications and training and everything else that you had to go through to get to that level. It’s not like we’re some clowns out there tipping, torches, throwing fire wherever we want to. There is a level of professionalism, expertise, and knowledge. Not only knowledge of your fire but so many of my firefighters, of my fire crews, my burn bosses, the folks riding the plans, they’ve been on this landscape all their life.

They’ve walked every inch of this landscape. They know what the wind is going to do at 1,600 and they know what it’s going to do at 06. They know it’s June and this is going on. This is going to happen because they’ve been here. They’ve seen it. The bottom line is we have all, as a culture, have got to find some way of getting a little bit comfortable with a little bit of risk because there’s a risk in doing something and there’s a risk in doing nothing. We can continue doing what we’ve been doing, leaving it alone, letting the forest continue to overgrow and suffer the consequences. We’ve seen what that looks like. We have examples to point to of what that looks like.

Maybe we should try a different approach. That, too, comes with those levels of risk, but we’re doing everything in our power to mitigate them as much as possible. It would be negligent on my part to say that we could get the risk down to zero. Not true. Not happening. There are going to be things that happen and it’s terrible. I wouldn’t want that on anybody.

I don’t know how to get around it. I don’t think any of us know how to get around it. There is going to be shit happening. We are doing everything in our power to mitigate that as much as possible. We know what happens when we leave it alone. We know. We’ve seen that. We’ve got the proof. We’ve got the empirical data on that. Now we need to try a different way, try a different set of risk factors.

There’s a risk in putting fire to the ground and tipping torch and utilizing fire, like natural starts for resource advantage or ecological benefit. Sometimes these things get away from us and that’s a part of the game. However, if we don’t take those risks now, I think the greater risk is going to be in the future. We’re going to have other Dixie fires. We’re going to have another August Complex.

Point to any major fire. When you’re having problems with 1 million-plus acres of fire, that’s not good. Granted, don’t get me wrong, this is not the first time over the course of a fire regime of fire history that we’ve had 1 million-plus acre burns. It’s nature doing its thing. It was going to happen. How do we not necessarily speed it up, not combat nature, but work with it?

Work in balance with it.

Look at the big burn of 1910, 3 million acres in three days.

Can you even imagine being on that line? Good lord.

That’s the thing that people know. No one ever realizes that that will happen again. Hopefully, it doesn’t. Hopefully, we can assist Mother Nature in taking care of herself. I would love to do that. Hold her hand, not pull her around in every direction necessarily, but like, “Do you want to burn here? Cool. Let’s do it. I’ll help you.”

I feel like that’s where I start to get a little bit philosophical because I feel like, for me anyway, part of the problem is that we as human beings have removed ourselves intellectually from seeing ourselves as part of the system. In some way or shape, we’re above it or next to it or whatever. The sooner we realize that we’re all part of the system and we should be working in harmony with it, to take care of it, to be those stewards that the land management agencies were established to be, then we’re going to start getting back on the right track.

Part of the problem is that we, as human beings, have removed ourselves intellectually from seeing ourselves as part of the system.

People talk about going into the woods and going into nature. We are all part of nature by our existence. If we start seeing ourselves that way, I think maybe we can start looking at our landscapes and our surroundings a little bit differently and start working to care for it a little bit more. This is a problem for all of us that we have to address.

That’s a tall order, especially for the people who are far removed from nature or think they are. A hurricane is still Mother Nature. An asteroid, the literal birth of the universe, that’s still nature.

That park you’re walking on your way to get your cup of coffee in the middle of downtown is nature too. It’s there. It’s around you. That goes back to that conversation that we were talking about. If you appreciate that and want to see the real deal, you have to let us save it. You got to let us do that work. That when you had enough of the rat race and the daily grind and you want to come out to the forest and pitch a tent and get away from everybody, turn off the cell phones, you got to let us do this work or there’s not going to be anything here for you to come to.

That is another thing too. It’s not the work that the Forest Service is doing. It’s all the collaborators. It’s the industry experts. It’s the ologists. It’s the people that have a chunk of our ranch land that’s grazing allotment. It’s all of it. There’s no one silver bullet. If we were to take all of these and put them to work, then we have something that we can scale.

We all like the idea of a silver bullet. You’re right. It doesn’t exist. No matter the problem, it doesn’t exist. It’s going to take everything that we’ve got. It’s probably going to take some things that we don’t even know about technologies that don’t exist yet. I love the fact that we’re using drones and UAS systems more and more in these operations whether that’s mapping the fire or dropping the balls or whatever, especially in some of our higher elevations in some of our steeper inclines.

Can you imagine using a drone 10 years ago or 15 years ago on a fire? We’ve come a long way in a lot of things and we will continue to. I hope we remain open to new technologies. I don’t think we’re going to ChatGPT our way out of this one, but hopefully, there are some tools out there that will help us get this work done.

I’ve seen the wildfire. I’m not going to say the wildfire industrial complex, but it is a wildfire industrial complex. You and I are very much a part of that. Even the show is not removed from that. It’s very well integrated into that. I see a lot of companies out there with the headline text or a lot of agencies out there with the headline text or a news, press release, whatever. They’re saying, “We want to stop wildfires.” Why are we hanging our hats on this lofty goal when it’s unnecessary and a goal that’s going to get us back to the first problem that we’re having now?

It goes back to getting people comfortable with risk. It goes back to that idea of if you have a lightning fire somewhere out there, we’ve got one right now in the forest that lightning struck a tree. The stars aligned on this one because it went into a predefined burn unit something we’d already done all the NEPA work on. We are managing that where it’s a prescribed natural fire and we’re managing that because that’s how Mother Nature takes care of herself.

That’s how she sends the forest trash collectors. Fire comes in and cleans up the forest floor. We have to be able to utilize those tools when they happen to us. There’s only so much work that every line digger out there carrying a torch is capable of doing. We’ve got to take advantage of those opportunities too when we have a lightning strike, especially when it’s somewhere away from population centers where we have all the resources available to us when the conditions are right.

One of the things that we talk about and think about, especially when we’re doing this work, is every single fire, if you think about it, is a managed fire. It has a plan. It has trigger points of when we’re going to execute a suppression strategy versus a managed-for-resource benefit strategy. They all have that trigger point.

Going back to those fire professionals, those folks in the background that you don’t see on the fire line that are doing all that planning. All the umpteen million acronym systems that all the different land management agencies have WFS, IROC, and everything else that helps us make those decisions. The bottom line, what it gets to is we’ve got to take advantage of those opportunities as well to, again, get that fire back on the ground that this ecosystem that is dependent upon it. Do what we can do. Do our part. When Mother Nature throws us a bone, we got to use it. We got to run with it.

When Mother Nature throws us a bone, we have to use it. We got to run with it.

It’s no surprise that if you have a catastrophic wildfire, if there happens to be an RX unit all on that wildfire, is that checking the box? Is that mission accomplished? Everybody can go home, wash their hands, like, “We don’t have to treat this because it’s been burnt in a wildfire.” That’s the thing I think that we need to be honest with ourselves from a management perspective. Is like, is that the goal? Was that the intended outcome of our prescribed fire to have it nuked off and then check a box? No, that’s not the goal.

You’re right. That’s why we work with our teams. That’s why we have our hydrologists, our soil scientists, and our botanists out there. It’s resource benefit, not resource destruction, 100% not resource annihilation. It’s a resource benefit. That’s all of it. That’s in increasing the health of the soil. How many of our soil people get geeky on soils for a minute? You want soil that has good porosity so that it can take the little bit of rain that we give it and properly sink it and nourish those plants.

There’s a whole world underneath our feet that we haven’t even literally scratched the surface of understanding. When you start talking about the mycorrhizal layer, when you start talking about the soil layers and all the ecosystems that live down there that contribute to a healthy ecosystem, we got to do it. We got to do it in such a way that takes care of the top and the bottom. What we see and what we don’t see. That’s what we’ve got to do if we’re truly doing this for resource benefit.

It wasn’t until recent history, especially with the work Paul Stanis is doing, that trees are literally using mushroom networks, and mycorrhizal layers to fucking talk to each other and share nutrients and resources. That’s crazy. Paul Stanis is a psychologist and there’s actual legitimate science out there saying that these forest ecosystems are using mycorrhizal layers, and mycelium layers to communicate with each other. Trees are talking to each other and sharing resources. That’s insane.

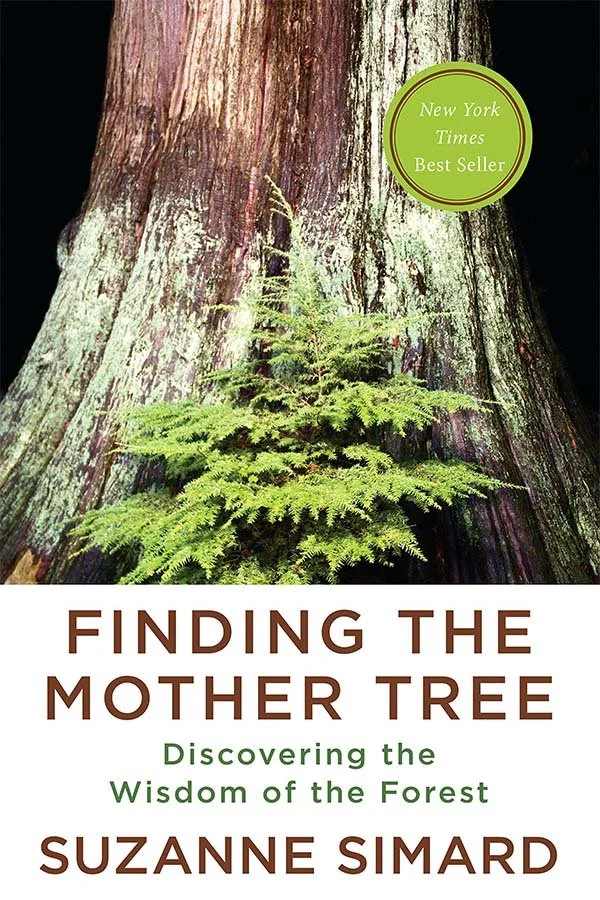

I can’t remember her name too, but there was a scientist up in BC. She did a book called Finding the Mother Tree and it was about oaks and it was that same thing. It’s those same oaks in different conifers, but how they use the mycorrhizal layers to not only talk to each other but intelligently talk to each other. Tell each other how to survive a pest, a certain pest. What do you need to do in a wildfire?

All it gave us was survival strategies. There’s so much more communication going on in these ecosystems than any of us are aware of. Orcas have figured out how to knock over boats because they’re tired of our shit. These systems talk to each other even if we don’t acknowledge it. If we don’t get our shit straight, they might start having some scary conversations about us.

If I start going down my dystopian science fiction reality worlds here and everything, all of a sudden, we’ve got the ends rising up and saying, “We’ve had enough of your shit, humans. We’re done with you.” Just go full-on fantasy. All of these things are in communications and the fact that we haven’t figured it out yet doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Only damn humans could have such hubris.